Bailey Bibliography

BAILEY, Chris L., Two Hundred Years of American Clocks and Watches:

Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. 1975.

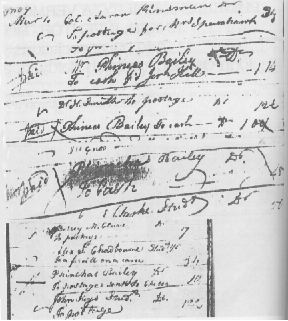

BALDWIN, Jedediah, Account Books and Ledgers, 1793-1811:

Special Collections of Baker Library, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire.

___, Papers--1794-1810., Handwritten Mss.; Receipts, Bills, Letters, Summons; &tc.

Special Collections of Baker Library, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire.

BULLETIN of the NAWCC, #85, Pg. 251; #119; Pg. 40; #144, Pg. 143; #187, Pg. 427; #211, Pg. 463; #227,

Pg. 703, & Pg. 741; #238, Pg. 607; #245, Pg. 488; #246, Pg. 46; #247, Pg. 126; #248, Pg. 215; #249,

Pg 312; #250, Pg. 380; #251, pg. 463; #261, Pg. 346; #289, pg. 219; #293, Pg. 723; # 294, Pg. 219.

Various references to Bailey, Baldwin, Dewey, Fyler, Hale, Hasham, and Osgood.

CARLISLE, Lillian Baker, Vermont Clock and Watchmakers, Silversmiths, and Jewelers, 1778-1878:

The Stinehour Press, Lunenburg, Vermont. 1970.

CHELSEA Centennial: Chelsea (Vermont) Centennial Committee:

proceedings of the centennial celebration of the

one hundredth anniversary of the settlement of Chelsea, Vermont,

together with the Orange County Veteran Soldier's reunion, September 4, 1884:

Sentinel Printing Company, Keene, New Hampshire. 1884.

CHELSEA Town Records, Book 7, Pg. 470.

CURRIER, Stanley P. and CLEMENT, Edgar T., History of Landaff, New Hampshire.

Currier Printing Company, Incorporated, Littleton, New Hampshire. 1966.

GILMAN, Marcus Davis, 1820-1880. The Bibliography of Vermont; or,

A list of books and pamphlets relating in any way to the state.

Printed by the Free Press Association, Burlington, Vermont. 1897.

GILMAN, W. S., Committee Chairman for the Chelsea Historical Society.

Chelsea, Vermont, 1784-1984, Shire Town.

Northlight Studio Press, Barre, Vermont. 1984.

HOPKINS, Persis Lorette. "A sketch of her father, Phinehas Bailey."

Bibliography of Vermont. Published in Gilman (supra).

Printed by the Free Press Association, Burlington, Vermont. 1897.

KERN, Charles W.,

God, grace, and granite : the history of methodism in New Hampshire, 1768-1988.

Published for the New Hampshire United Methodist Conference by Phoenix Pub. Canaan, N.H. 1988

LEE, John Parker, Uncommon Vermont: The Tuttle Company, Rutland, Vermont. 1926.

LORD, John King, A History of the Town of Hanover, New Hampshire:

Printed for the town of Hanover by the Dartmouth Press, 1928.

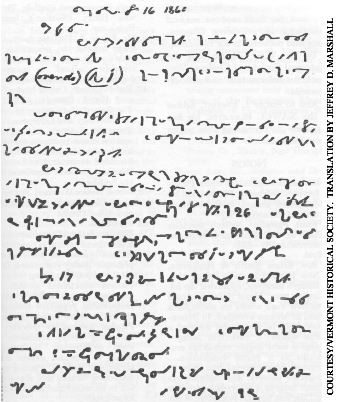

MARSHALL, Jeffry D. "Occasional paper Number 9:

The life and Legacy of the Reverend Phinehas Bailey."

Center for Research on Vermont, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, 1985.

MEMOIRS of Rev. Phinehas Bailey, written by himself.

Incomplete 55 page typescript transcribed 1902 by Louisa Bailey (Mrs. Joel F.) Whitney.

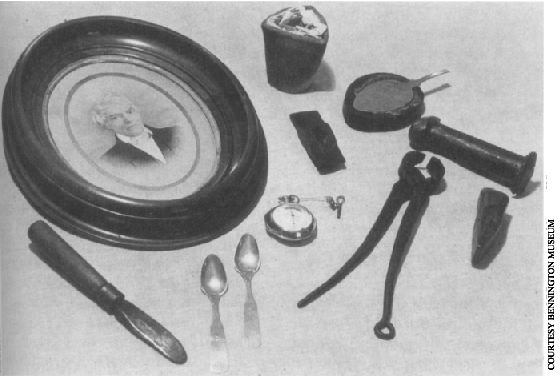

Courtesy the Vermont Historical Society.

MEMOIRS of Rev. Phinehas Bailey, written by himself. These five pages were

evidently edited out of the Vermont Historical Society typescript

(perhaps in an effort to remove the family's domestic difficulties

from the public eye) and are found in this typescript (transcriptionist unknown)

held in the collections of the Bennington Museum.

Courtesy the Bennington Museum.

NEW HAMPSHIRE PATRIOT [Concord, New Hampshire], 8 January, 1811. New Hampshire

Historical Society Collections.

PARSONS, Charles S., New Hampshire Clocks and Clockmakers:

Adams-Brown Co., Exeter, New Hampshire. 1976.

TAVES, Ann, Ed., Religion and domestic violence in early New England:

The Memoirs of Abigail Abbot Bailey:

Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana. 1989.

TREVELYAN, George Macaulay, History of England:

Doubleday & Co. Garden City, New York. 1953

WHITCHER, Rev. William F., History of the Town of Haverhill, New Hampshire.

Rumford Press, Concord, New Hampshire. 1919.

WHISKER, James Biser, Pennsylvania Clockmakers, Watchmakers, and Allied Crafts:

Adams Brown Company, Cranbury, New Jersey. 1990.

WHITNEY, Louisa M. (Bailey), A Father's Legacy: unpublished typescript

(transcriptionist and date of transcription unknown) manuscript.

An uncritical, and highly edited biographical treatment of

Phinehas Bailey. Courtesy the Vermont Historical Society.

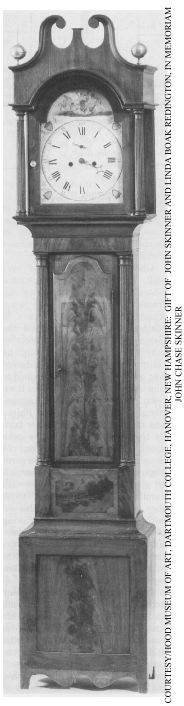

ZEA, Philip, Clockmaking and Society at the River and the Bay--Jedidiah and Jabez Baldwin, 1790-1820:

Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife. Annual proceedings. Boston University: Boston. 1981.

___, To making one of Saturn's moons: Jedidiah Baldwin and the Urbanization of the Upper Connecticut

River Valley, 1793-1811.

Typed manuscript in the Special Collections of Baker Library, Dartmouth

College, Hanover, New Hampshire. 1979.

).

This is probably correct but it is the last way I should have thought of.

).

This is probably correct but it is the last way I should have thought of.