Hiram Todd Dewey, Clockmaker,Vintner & Snake Oil Salesman

© Donn Haven Lathrop 2008

While working through several studies of various New England makers, and their work in that section of the country, I noticed that many of these makers or their relatives, apprentices, or partners were emigrating to the Midwest. Research is a strange mistress---the more one knows, the less one apparently knows. Hours spent in the musty depths of a library have a bad habit of leading one astray, simply because so much other data is discovered while searching for references to the particular subject of one's interest. I also wandered into the Midwest...

Background...

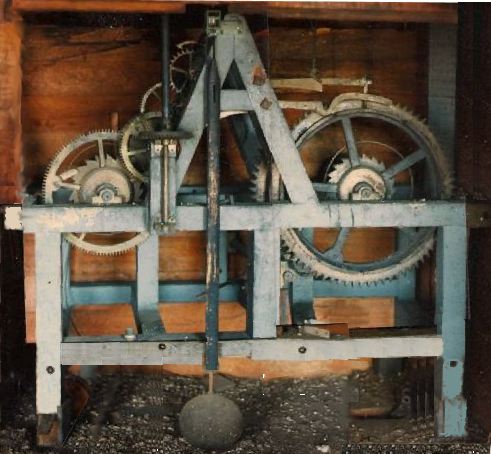

Therefore it happens that I found that the subject of this paper was born 13 July, 1816, to Jeremiah and Orinda (Todd) Dewey in Poultney, Vermont. His father was a clockmaker who began his career in 1808 in Middlebury, then in 1820 moved to (what was evidently a rather unproductive) East Randolph, and then on to Chelsea in about 1823. It is interesting that Phinehas Bailey of Landaff, New Hampshire, an apprentice to John Osgood in Haverhill, New Hampshire, and journeyman to Jedidiah Baldwin in Hanover, New Hampshire, had moved to Chelsea in 1808, "[because I had] learned that there was one Nathan Hale who formerly worked at the clock business who had some tools to sell." Bailey then struck a bargain with Hale in a partnership wherein Hale would provide the shop and the tools and stock, and Bailey would make clocks "by the halves." But, by 1816, the flood of cheap wooden clocks (Eli Terry probably drove the ante-penultimate nail in the hand-made movement's coffin) had begun to flow northward from Connecticut, and Bailey's market for brass clocks collapsed. His personal claim in later years was that he had been the "last brass clockmaker in New England" when he quit the business in 1816. I feel that Bailey was already somewhat out of touch with reality when he made his claim to be the "last clockmaker in New England". He was by this time on the doorstep of the development and subsequent publication of his unique shorthand method, while simultaneously redefining his life more toward religious pursuits.

In reflecting on the apparent lack of business in this particular area, this dropping out of clockmaking isn't too surprising. Perhaps as an illustration of this apparent lack of business for the local maker: It has been noted that as late as 1848 in Strafford, Vermont, only 24 men---4 per cent. of the grand list---were taxed on their pocket watches, and it's estimated that there were, at the most, 50 clocks in the town. This Upper Valley (as it is known today) region of New Hampshire and Vermont does not seem to have been kind to the clockmaker---Martin Cheney moved from Windsor, Vermont, to Montreal in 1809; Jedidiah Baldwin left Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1811 after a rather unrewarding career; Phinehas Bailey quit the business entirely in 1816; Stephen Hasham of Charlestown, New Hampshire, made his living principally as a builder and architect (it took him nearly ten years to sell his first four tower clocks), and the Dewey family left for Ohio in about 1830-31.

However, some makers in this Upper Valley area of New Hampshire and Vermont continued to work profitably, well into the late 1830's. For instance, Bailey's own master, John Osgood, made a gallery clock in 1838, (very likely his last clock---he died on 29 July, 1840, at the end of a clockmaking career covering some 45 years) that he presented to his church in Haverhill, New Hampshire.

Biography...

The Early Years...

In 1829, the 13-year old Hiram began working---obviously an apprenticeship---in his father's shop, only to have this apprenticeship interrupted within a year or so. The Dewey Family History does not record a precise date, but in about 1830-31 Jeremiah Dewey moved his family from Chelsea, Vermont, to Sandusky, Ohio. Notwithstanding the interruption, by 1836 Hiram was 'given his time', and first engaged in the jewelry business at Perrysburg, Ohio, on the outskirts of Toledo. He later removed to Fort Wayne, Indiana, and there continued in the jewelry business. While in Fort Wayne, he married on the 23rd of November, 1838, Susan Lanfrey Stapleford, the daughter of William and Elizabeth (Defuty) Stapleford. She was born on the 28th of December, 1818 at New Castle, Delaware, and died 25 May, 1898, at age 79 at Brooklyn, New York. Dewey served in the Wayne Guards as First Corporal in 1841, when the militia was organized. Two of his five children were born in Indiana, but by 1843, according to the Dewey Family History, he had returned to Sandusky. In the 1850 census, he is listed as 'watchmaker', with no apparent assets, and is later listed in the 1855 Sandusky Directory as a dealer in jewelry and watches. According to this Directory, Hiram continued in this business in both Sandusky and Tiffin (about 50 miles to the southwest) until about 1861---by this time he had added boots and shoes to his inventory. It is of interest that in the 1850 census he was listed as without assets, yet, by 1860, he had obviously prospered: His real estate holdings were listed at $4,100, and his personal property at $4,500. Also resident in his house was a (probable) maid named Lucy, born in Ireland.

The Vintner...

The Dewey Family History records:

"[In] 1857, ...he purchased a farm one mile from [Sandusky], and planted therein a vineyard. This was the pioneer vineyard in northern Ohio, on the main shore of Lake Erie. There were already small vineyards on Kelley's Island (an island just offshore in Lake Erie). Mr. Dewey's success was immediate: by 1860 his vines were in full bearing and were a wonder to the people in the surrounding country: hundreds of visitors came to inspect the vineyard, people became enthused, and business men, professional men, school teachers, and others began to buy land upon which to plant vineyards, and property in the neighborhood advanced from $75 to $400 per acre. The idea had hitherto prevailed that grape culture could only be successfully conducted on an island. Mr. Dewey first sold his fruit for table purposes, but in 1862 he began to make wine, and put up 4,000 gallons, the following year 15,000, and progressed from year to year, until the business of wine making absorbed his entire attention. In 1865 he opened a house in New York for the sale of his wines."

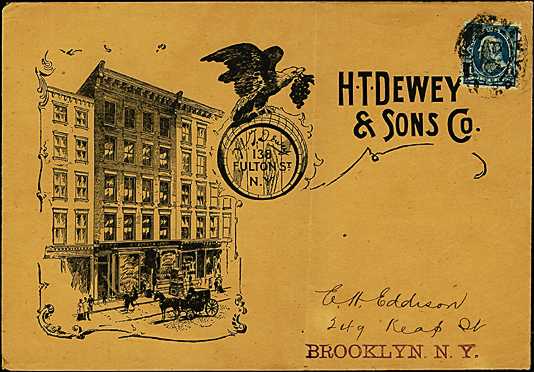

Figure 1. A postcard showing the H. T. Dewey & Sons building in New York circa 1898.

"There then existed a great prejudice against American wines, and the outlook was discouraging. Success was at first slow in coming, and it was hard to do away with the popular prejudice then existing. But in time the American product came to be appreciated, and Mr. Dewey found ready and increasing sales for his wine, and the pioneer wine house has established for itself a name and trade..."

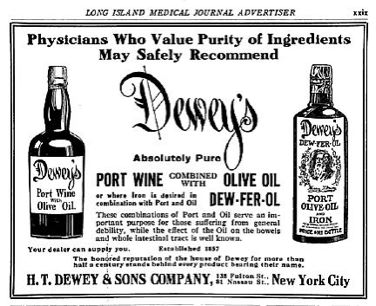

Figure 2. A bottle from Dewey's winery.

As late as 1920, H. T. Dewey & Sons---Jeremiah, George, and Hiram, Jr.---were wine merchants at 138 Fulton Street in New York City. Dewey evidently found the New Jersey soil in the vicinity of Egg Harbor accomodating of the cultivation of a vineyard, as he planted one that did well. The company is known to have flourished through the 1920's, until Andrew Volstead's Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution caused it to fade from the wine business. Hiram Todd Dewey, clockmaker and vintner, died on the 11th of July, 1901.

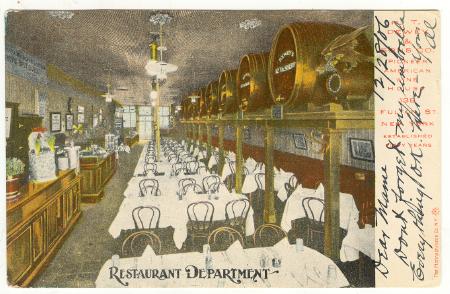

Figure 3. The Restaurant Department of HT Dewey & Sons,

Wine House in New York City. A hand-tinted postcard from 1906.

The Snake Oil Salesman...

Dewey did, however, concoct some rather interesting potions which, rather naturally, featured his wines. One of these was "Dewey's Emulsion" of cod liver oil and port wine, recommended for: "Coughs, colds and general run-down conditions, also for the relief of bronchial troubles and irritations of the mucous membrane surfaces"---plus it was also "beneficial to convalescents after pneumonia, the grippe, and influenza." The bottle blurb concludes with: "The new formula retains all of its vitamin elements---flesh producing and tissue building, blood making and digestive advantages."