Very little about Nathan Hale has been published in the

BULLETIN.

The earliest reference is by James Gibbs, (#184, Pg. 427), who names him a

native of Pindge (sic), New Hampshire, and repeats the assertion

that he apprenticed with Stephen Hassan (sic).

Other references are those in BULLETINs

#250 and #251, the former of which mentions the existence of a Hale

account book, and the latter mentions that several Hale clocks are known

to exist, and BULLETINs #293 and #295;

references to his alleged apprenticeship and his relationship with

Orsamus Roman Fyler.

This account book of the mercantile firm of Nathan and Harry (his

youngest brother) Hale, covering the years 1804-06 in Windsor, now in

the collections of the Windsor [Vermont] Public Library, has very few

references to either clocks or watches. The most interesting entries in

this account book concerning any sort of clock or watch work are

detailed below.3 The first is an account debit against

Nathan in August, 1803, of $5.33 for clock weights bought from someone

named Marsh. In October his account was debited by $51.81 for "12 plain

12 inch clock faces" purchased from Martin Cheney, his erstwhile

primary competitor in Windsor. In November he was credited with an

unspecified amount for cleaning a clock. He was credited with $24.00

for a watch sold to a Captain Bennet in November, 1804. In April of

1805, he was credited with $56.62 for a clock (very likely a tall clock)

sold to a 'Houghton.' In June, 1805, he was debited with $5.58 "to

goods Bot in Boston for clockwork." The following month, he was

credited with 50¢ for having cleaned a clock the previous winter. In

November he was credited with $1.50 for a clockglass, and debited for

$10.03 for "Clockwork bought of Tuckerman & Hazen4 12 Oct."

3These data were excerpted by Charles

S. Parsons, 16 April, 1987, at the Windsor Public Library, and are

available at the NAWCC Library and the American Clock and Watch Museum.

4If anyone, anywhere, knows anything of the firm of Tuckerman

& Hazen, the author would really appreciate the information. An

Edward Tuckerman is listed as a merchant in the Boston City Directory

with a residence at #15 Franklin Place. A George W. L. Hazen is listed

elsewhere as a watchmaker and repairer, ca. 1858 - 1869.

2

It is extremely curious that a clockmaker would so quickly yield his

position to his competition, to the point that he referred his own

customers to Cheney, and later purchased the 12 dials from him. One

wonders just what he did with these dials--were they used on the few

known tall-case clocks? Hale is not debited with the usual purchases of

steel, brass, glass, clock cases, and other items one would expect of

an active clockmaker. Further, why did he purchase "clockwork[s]?"

There are apparently no more than ten clocks of various types which are

known to have been made by Hale. From the above record of his

purchases, and his apparent horological inactivity, the suspicion arises

that he may have purchased the works, the dials, and the cases, put

everything together, and sold the result as a 'Hale.' Let's assume that

he was credited with 50¢ for the "unspecified amount" above. Nathan's

net income in the two year period covered by the account book was

$10.37. For someone who is an alleged "clockmaker," that's not a whole

lot of work on and with clocks, is it?

It's also interesting that Hale was paid $56.62 for a clock. Jedidiah

Baldwin, just up the Connecticut River in Hanover, New Hampshire,

charged $33.00 for an uncased clock, $53.00 for a cased clock--and he

had to make the movement. If Hale paid $4.32 for a dial ($51.81/12),

$10.03 for the movement, $5.33 for the weights, and $12.00 for the case

(as Baldwin did), his costs were $26.68, with little labor involved. A

$30.00 profit with little labor isn't bad at all.

It is even more difficult to believe that Nathan Hale served an

apprenticeship with Stephen Hasham, regardless of Thomas Hale's (Harry

Hale's son, and nephew to Nathan), statement in the keynote address for

the Chelsea Centennial Celebration5 in 1884. A corroborative

note may be found in the 1790 and 1800 census figures for Charlestown,

New Hampshire, and Windsor, Vermont:

1790: Stephen Hasham; 1 male 16 to 25; and 3 females. (The male [age

16+] is Stephen, whose first son was born in 1792--no apprentices.)

1800: Stephen Hasam (sic); 2 males less than 10; 1 male 10 to 16;

1 male 16 to 25; 1 male 26 to 45: 3 young females and wife.

1800: Hale, Nathan, Windsor County, Vermont.

5. CHELSEA Centennial:

Chelsea (Vermont) Centennial Committee:

Proceedings of the centennial celebration of the one hundredth anniversary of the

settlement of Chelsea, Vermont, together with the Orange County Veteran

Soldier's reunion, September 4, 1884.

3

The large number of males in the Hasham household in 1800 would indicate

that there were at least two non-family (Hasham's sons would have been 8

and 3 in that year) members in residence at that time--very likely

apprentices. It is much more likely that these (possible) apprentices

were learning either the carpenter's or bricklayer's trade than

clockmaking. Hasham is given his place in Charlestown's history as an

architect and builder, rather than as a clockmaker. In reflecting on

Hasham's proclivities6, I would deem it highly unlikely that

the newly-wed (on 27 September, 1787) Stephen either wanted or had an

apprentice in his house.

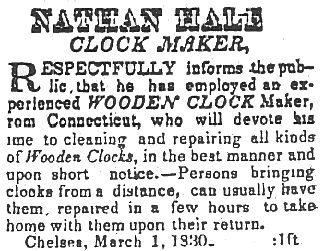

After their sojourn in Windsor, the brothers Hale then surfaced in Chelsea,

Vermont, where land transactions7

are recorded for Nathan and Harry Hale in 1807. Oddly enough, census

data does not place Nathan in Chelsea, Vermont, until 1820, by which

time, according to the Memoirs of Phinehas J. Bailey,

he had long since quit the business of clockmaking8.

Phinehas had moved to Chelsea in 1809 after his seven-month journeyman

service with Jedidiah Baldwin of Hanover, New Hampshire, "...[because I

had] learned that there was one Nathan Hale9 who

formerly worked at the clock business

(author's emphasis) who had some tools to sell." Bailey struck a

bargain with Hale in a partnership wherein Hale would provide the shop,

the tools, and the stock, and he would make clocks "by the halves" in a

partnership that lasted from 1809 to 1816-17. Bailey finally quit the

business in the face of low-priced competition from Connecticut clocks,

claiming that he was "the last brass clockmaker in New England."

6. Stephen Hasham was married twice.

His first wife bore him five children during a 54-year marriage. Less

than four months after her death, Stephen remarried--his bride was a

school teacher of 23--and the couple produced five more children. His

daughter Emily was born when he was 86.

7. Chelsea Town Records, Book 7, Page 470.

Chris Bailey, in Two Hundred Years of American Clocks and Watches

mistakenly places Hale in Chelsea in 1797.

The very short note by James Gibbs in

NAWCC BULLETIN,

No. 184, Page 427, is wholly inaccurate.

8. See Donn Haven Lathrop, "Phinehas Bailey, a Vermont Clockmaker,

Tinker, Inventor, Minister..."

NAWCC BULLETIN,

No. 315, (August 1998): Page 461.

9. "Memoirs of Reverend Phinehas Bailey, written by himself"

and Donn Haven Lathrop, "Phinehas Bailey, A Vermont Clockmaker, Tinker,

Inventor, Minister..."

NAWCC BULLETIN,

No. 315 (April 1995): Page 461.

4

Nathan Hale's own career as a clockmaker must have been rather short,

perhaps covering only the fifteen years--if that--from 1791 to 1806.

There is no specific record of his apprenticeship, whether as a gold- or

silversmith, or as a clockmaker. Parsons and Carlisle both claim (but I

suspect that they might be quoting one another) that Hale apprenticed

with Stephen Hasham of Charlestown, New Hampshire, but Hasham is not

known to have worked in either gold or silver. Hale may have

been one of Stephen Hasham's apprentices, but the only known basis for

this claim derives from the above-mentioned keynote address for the

Chelsea Centennial Celebration in 1884. Thomas Hale, by then the editor

and part owner of the Fitchburg Daily and Weekly Sentinel, in

Fitchburg, Massachusetts, was at 71, too frail physically--and one

wonders about mental frailty as well--to give the speech himself. Edwin

A. Battison (pers. com.) has concluded from his studies of New England

makers and their clocks that Hale more likely apprenticed with the

Hutchins'; therefore this minor controversy may continue to rear its

questioning head. And let us not forget that Peter Davis, a clockmaker

listed in the History of Rindge , was in Rindge in the 1780's.

However, Hasham is thought to have arrived in Charlestown in 1785 (Hale

would have been 14), married in September, 1787; his first child was

born in early 1789. The very idea that Hasham had an apprentice

underfoot during these years verges on the absurd. It is also

interesting to note that in the 1790 census, when Hale would have been

181/2 years old and embroiled in the toils of an apprenticeship,

that but one

male over 16--Stephen himself--is listed in the Hasham household. If

Hale did indeed apprentice with Stephen Hasham, that apprenticeship

would have been much shorter than the expected norm, and he would have

been 'given his time' in the very late 1780's since he advertised that

he was in business as a clockmaker and goldsmith in Rindge by 1791.

His first advertisement reads:

NATHAN HALE, Clock-Maker and Goldsmith, Begs leave to inform

the publick, that, at his shop, near the meeting house in Rindge,

persons may be supplied, on short notice, with warranted Clocks of the

best kind, either with or without cases. Also Gold and Silversmith's

work, of various kinds, made and repaired--as Gold Necklaces--Silver or

plated Buckles, may be made to any pattern, &c. &c.

Customers may depend on being served with honour and fidelity.

Cash given for old Gold, Silver and Brass.

Thomas's Massachusetts Spy: or, The Worcester Gazette,

December 22, 1791.

5

One would expect that Hale, working less than twenty miles north of his

alleged master, would be likely to do more business in the local area,

as did both Martin Cheney in Windsor and Jedidiah Baldwin in Hanover,

New Hampshire. That he did quite a bit of his 'shopping' in Boston,

some 110 miles to the southeast, is not unusual. Local purchases of

clock cases, "old Gold, Silver and Brass," advertisements for an

apprentice, etc., would certainly point to serious activity in

clockmaking in both Windsor and Chelsea, but these indicators are

non-existent since that one advertisement in 1796, in direct comparison

with advertisements by Martin Cheney. Baldwin did business with firms

in New London, Connecticut, and New York City as well as with customers

in the Hanover area--but his primary activity was local.

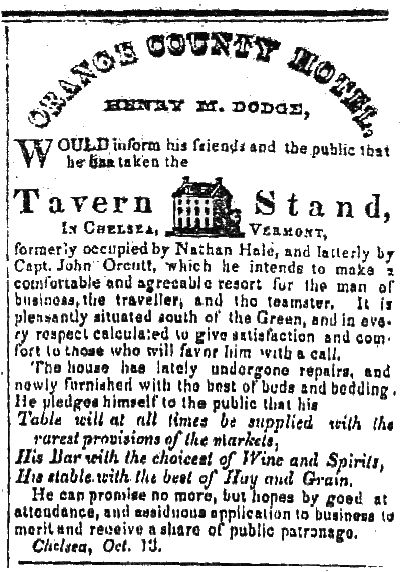

The History of Chelsea, (Vermont) 1784-1984,

notes that Nathan and Harry Hale came to Chelsea in 1807, based on the

above-mentioned land records, yet only mentions in passing that Nathan

was a clockmaker. One has to take mild exception to Mr. James T. West's

statement10 that Hale "supplemented his clockmaking income

by running a hotel"; it was much more likely the other way around--Hale

was a merchant and innkeeper who bought his movements, dials, and

cases. Perhaps he should be thought of as a "clock assembler," rather

than as a clockmaker. It would be extremely interesting (and perhaps

startling) to examine the movements of his known clocks, in a search for

the "signature(s)" of the maker(s). A resolution could possibly be

achieved through an examination and comparison of known movements by

these various makers--Hale, Hasham, and Hutchins. And who knows?

Perhaps the firm of Tuckerman and Hazen as well...

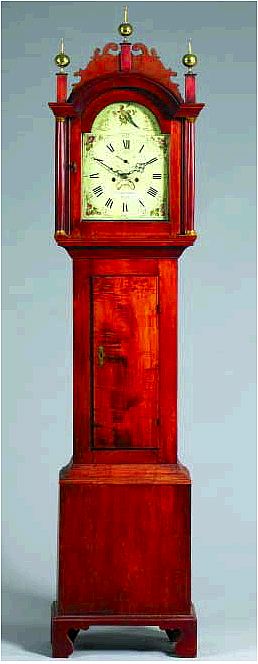

It is telling that the illustrated tallcase clock (Figure 1) has a

movement that appears to be an import, and that the false plate (and

very likely the dial) are by Wilson of Birmingham, England. Hale is not

known for his cabinetmaking skills; therefore, the case was also likely

a purchase. It is an apparent characteristic of Hasham's clock

movements that the pillars were riveted into the back plate in such a

manner that the ends of the pillars protruding from the plate are domed:

the pillars on this clock have filed-flat rivettings. Perhaps slim

evidence, but there are too many examples of the apprentice faithfully

emulating the master, and this obvious variance, the 12-inch dials

purchased from Cheney (this clock has a 12-inch dial) and the "Clockwork

bought of Tuckerman and Hazen 12 Oct., [1805]" all point to Hale as an

assembler, rather than a maker.

10.

See James T. West, "Vermont Clockmaker Jeremiah Dewey,"

NAWCC BULLETIN,

No. 295 (April 1995): Page 223.

6

|