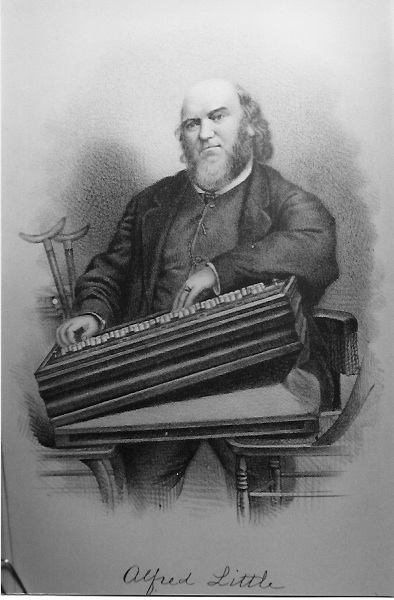

Figure 1. An engraving of Alfred Little, a virtuoso of the seraphine.

© Donn Haven Lathrop 2009

Benjamin Morrill was a clockmaker, scalemaker, and musical instrument maker who lived and worked in Boscawen, New Hampshire, during the first half of the 19th century. Boscawen, just to the northwest of Concord, was first settled in 1733 and took its name from Admiral Lord Edward de Boscawen, whose Norman ancestors had come to England in 1066 with William the Conqueror. The Admiral was the commander of the English fleet which nearly annihilated the French Navy off the French coast in the closing years of the French and Indian War.

Very little is recorded of Morrill's life---as a solid and stolid citizen and businessman in the town, he wasn't given to any particularly odd behaviors or habits which would enshrine him in the memories of the citizens of Boscawen. He lived in the first frame house built in Boscawen, a house built in about 1761 by his grandfather, the Reverend Robie Morrill. All the Morrill family's eccentricities seem to have settled themselves in this minister, who once expounded for two solid hours on the pronoun, "it"; startled his congregation by exclaiming "There goes a mouse!" in the midst of another profound exhortation, and another time asked someone in his dozing congregation, "My friend, won't you please punch that man who snores so loud, for if he goes on at that rate he will wake up my wife." A 1755 graduate of Harvard, he was minister of the Congregational Church in Boscawen for five years. He resigned his pulpit in a dispute with the town over his pay, and then taught school for many years.

Benjamin Morrill was born in Boscawen on 16 January, 1794, the fifth child of Samuel and Sarah Morrill. The Morrill name had been closely associated with Boscawen from the day the Rev. Robie Morrill was 'settled' as the minister in 1760. Benjamin very likely received the usual education of the day, both religious and civil, but had a natural bent for, and a creative skill, in mechanical matters. The Morrill genealogy is quite specific about his having been "a man of great ingenuity"---he is considered by some to have originated the New Hampshire mirror clock. Where and whether and with whom he served an apprenticeship is not known. Donald K. Packard mentions the possibility that both Morrill and Joseph Chadwick served their apprenticeships under Timothy

1

Chandler (citing resemblances in Chandler's and Morrill's clock movements and clock cases), but they could have been apprenticed to Nathaniel Peabody Atkinson, at work in Boscawen in 1807. Chadwick, who later married Benjamin's older sister Judith, was his contemporary and probable competitor in Boscawen, a clockmaker who also made tall-case and mirror clocks. Morrill had a deep interest in music (as did his contemporary, George Handel Holbrook); in 1821 he and several others organized the Martin Luther Society, "A Society [for] the Cultivation of Music of a Higher Order", in which he sang for many years. In 1829 he was authorized to "raise money for the purchase of an organ for the church", and when clockmaking became unprofitable began the manufacture of musical instruments.

On 22 November, 1819, he married Mehetable Eastman, the daughter of Simeon and Anna (Kimball) Eastman, of Landaff, New Hampshire, and by her had two children, Lucretia, born 1822, and Franklin L., born 1824. Both of these children died in August of 1825---no cause of death recorded. Mehetable died on 6 July, 1828, in Boscawen. Morrill remarried six months after his first wife's death, to Mary Choate of Derry, New Hampshire. They had two children, Franklin Choate, born 1836, and Mary Frances, born 1843. In the 1850 census Benjamin was identified as a 'Clockmaker', with an estate of $2000---a fortune in that day. His wife unaccountably gained a year in age in this census. His nephew, Reuben Morrill, is listed as a resident in Benjamin's household. Reuben may have been an apprentice who later left his name in several New Hampshire clocks1. In 1860 Mary C. Morrill is listed as head of the household---and somehow managed to lose 11 years on her recorded age. Benjamin Morrill died 21 April, 1857, three months after his 63rd birthday.

MORRILL'S KNOWN TOWER CLOCKS:

HENNIKER and DOVER, NEW HAMPSHIRE

Very little has been written of Morrill's tower clocks. The primary concentration to date has been on his conventional tall-case and innovative 'sidewheeler' mirror clocks. This article will focus on his equally innovative tower clocks. Charles S. Parsons wrote this thumbnail sketch of Morrill's business activities:

1 See the question posed in the "The Answer Box", NAWCC BULLETIN Whole Number 83, Page 61, about 'R. Morrill' signatures found in several clocks. Benjamin's cousin, Reuben Prentice Morrill, is listed as still living at home in this same census record.2

"Benjamin made mirror, banjo, shelf, tall and tower clocks...The first [tower] clock set up in Dover, New Hampshire, was made by him for the First Parish Meeting House at a cost of $300. He also provided one for Henniker [New Hampshire]. When clockmaking became unprofitable he made scales. A small beam (scale) with "B. Morrill-Boscawen" die stamped on it would indicate that he made platform scales with a capacity of 100 pounds. About 1840 to 1850 (regardless of his listing in the 1850 census as "Clockmaker") he made musical instruments such as melodeons and seraphones (sic)."

A melodeon is a small---2 to 21/2 octave---vacuum-operated reed organ developed in the first half of the 19th century. The required vacuum is developed with foot pedals, which the player has to pump very rapidly. For that reason the instrument is perhaps not the best source for 'serious' music, unless the musician's lower body is concealed from the audience's view---it's like watching someone run the 100 yard dash---sitting down! There were many other reed instruments which were popular at that time, but they were operated by air pressure---the timbre of a reed instrument's voice changes considerably if it is generated by vacuum rather than by pressure. The seraphine is also a small, vacuum-operated reed organ with a range similar to that of the melodeon, invented in England about 1830. It's rather difficult to play well, because it's pumped by pushing down on the left side of the instrument with the left arm while the left hand simultaneously plays the bass line "keys", which are mounted on the left side of the instrument. This is another instrument that is best only heard---definitely not seen, because of the unusual posturing of the musician---by modern audiences.

Too many tower clocks have unfortunately, and sometimes seemingly unaccountably, disappeared without a trace. We should remember that public clocks were once considered a necessity, indeed, they were everyone's pocket watch. A town clock that didn't keep time properly was summarily discarded, regardless of its historical (to us) value. For some reason, Parsons recorded a great deal of data on Morrill's Henniker clock, but gave rather short shrift to the Dover clock, which seemed to have disappeared into thin air.

3

The History of the HENNIKER Clock

The Henniker town history records that the clock was placed (probably 1834 - 35; no specific date can be found) in the Congregational Church which was rebuilt in 1834 following a fire: "The house was furnished with a bell (by the Revere Copper Company) which was raised to its position the day the building was raised May 8, 1834...and a clock, built by Mr. Morrill, of Boscawen, and an organ...". Thirty four years after the clock was removed from the church in 1949, it was given to the American Clock and Watch Museum in Bristol, Connecticut, by the late Frederick Mudge Selchow.

The History of the DOVER Clock

A small compendium of "Notable Events in Dover" records for the first of May, 1835:

"This day a steeple clock, built by Benjamin Morrill of Boscawen, NH, was set going in the tower of the First Parish Meeting House. The cost of the clock including dial (author's emphasis, but probably a single dial, for reasons later discussed) and fixtures about $300. This is the first steeple clock ever set up in Dover. This clock paid for by subscriptions from various persons, citizens of Dover, and was put up in the tower of the meeting house by consent of the Parish. Mr. Asa A. Tufts and Mr. Geo. Quint took care of it for several years, when the selectmen agreed to pay someone to keep it going." (Tufts Record)

After the several years of care by Mr. Tufts and Mr. Quint, payments to various people for the care of the clock appeared in the selectmen's records. Yearly payments ranged from $12.00, beginning in 1844, to $26.50 in 1931, with an unexplained hiatus in 1869 - 71. The following entries were noted beginning in 1867:

1867 N. H. Breard care of Town Clock 10.00

1868 No entry on care of the clock.

1869 Cha's W. Brewster, winding and caring for old clock 12.50

Charles W. Brewster, winding and repairing old Town Clock '68 and '69 (author's emphasis) 24.00

1870 No entry on care of the clock.

1871 C. W. Brewster, care of clock, 5. 00

The abrupt shift in reference to the "old Town Clock", the lack of entries in 1868 and 1870, and the reduced payment in 1871 suggests that the clock had either had a catastrophic failure and extensive repairs, or had been replaced, but there are no town or church records of either major repairs or replacement. Further, in reading through the histories of Dover, the suspicion quickly arose that the clock might have been repaired, but later destroyed in one of the many fires that had occurred in the town in the 160 years since the original installation of the clock. Particularly devastating fires were recorded in 1889, 1907, 1933, and 1950---the last destroyed the Town Hall and much of the downtown area. That no one had sought out the clock to document it further contributed to the feeling of unease. The usual fate of many of these old clocks, even if they have managed to survive through fire and neglect, has been a quick trip to the dump, and replacement by a more modern tower clock, usually installed soon after the visit of a high-pressure salesman representing the likes of Seth Thomas or Edward Howard.

BENJAMIN MORRILL's

TOWER CLOCKS

Benjamin Morrill was one of the first American clockmakers to design a flatbed tower clock with a unique built-in vertical drive to a transmission capable of driving more than the usual maximum of three dials. The only other clock I know of is the 1847 clock attributed to Hiram Todd Dewey installed in Lebanon, Ohio. Early flatbed clocks (such as those of Abel Stowell, Sr., Stephen Hasham, Major George Holbrook, George Handel Holbrook, and Simon Willard) were placed in their steeples on a level with the outside dials. Because of their simple transmissions, these clocks were best adapted to driving dials behind and to the left and the right of the clock. Morrill developed a clock-frame-mounted, bevel gear driven (from the second arbor) vertical shaft to a post-supported cluster of bevel gears (the transmission) at any height above the clock frame. This transmission could conveniently drive up to four dials without any major modifications to the basic design of the clock. An 1823 Hasham in Troy, New York, for instance, has a yoke pinned on an extended pivot2 of the second wheel arbor to permit of driving four dials, but for

2 Modifying the flatbed clock in this fashion summarily removed its greatest attraction---simplicity and ease of service, adjustment, and repair---as well as making it nearly impossible to set the outside hands simultaneously. See The Amazing Stephen Hasham, NAWCC BULLETIN # 293. Similarly, Holbrook's strike "fan", buried beneath the table, is difficult to service.4

some reason, the clock only drove the traditional three dials, even though one dial was driven by the add-on yoke! Morrill made no simple provision for setting the outside dial hands. The usual method of hand-setting on most clocks of this era is to slide either the escape wheel or the pallets out of engagement, and then "freewheel" the train. The sliding arbor involved was held in place for normal running by a weighted shutter or a spring-loaded pivot stop. Setting the outside hands on a Morrill clock requires that the crutch be disengaged from the pendulum, one of the pallet arbor bushings removed, the pallets disengaged---literally left dangling---and the train then "freewheeled", a dangerous and cumbersome procedure. It is even more cumbersome because all of the above has to be done at the back of the clock, while the setting dial is at the front of the clock. Pinwheels with obviously replaced pins are the norm. None of Morrill's known tower clocks have ever had more than three dials, and the Dover clock had only one dial for quite some time. This clock later had an extremely unusual motion-work-based transmission installed to drive its three dials, a system which could have been modified to drive four dials, had that been desired. Morrill's tower clocks are unusual in having the second wheel turning at 2 revolutions per hour, which requires either larger great and second wheels with more teeth, or a greater fall for the time weight. His contemporaries designed their wheel trains so the second wheel made 1 full rotation per hour. Morrill also was the first to use a unique horizontal strike rack which was pulled against the snail by a cranked weighted arm at the warning---did Howard copy Morrill? Morrill placed the ratchet for the strike fan on the collet for the third wheel in the strike train, rather than on the fan itself, a location used nearly 150 years earlier by Thomas Tompion. His tower clocks were built on a wood frame with mid-beam construction, used a pinwheel escapement, and contained a rather high percentage of cast iron. Many researchers consider the use of cast iron to be a reflection on the economy of the early 1800's, but Lord Grimthorpe noted that cast iron is considered an excellent material for clock wheels. Morrill's use of cast iron varied from clock to clock, but on different examples, the great and the second wheels, the pendulum bob, the winding drum endcap and ratchet, the winding jack gears, and even the motion work wheels have been made of cast iron. Nearly all of his clock wheels have some form of decorative spoking, most of the brass bearings are decorated; and horizontally split bearings are found on the winding drum arbors and on some of his motion works.

5

The HENNIKER Clock Chronologically (as far as we know), the Henniker clock, which is now in the American Clock and Watch Museum in Bristol, Connecticut, is Morrill's second. Parsons claims an 1835 installation date, which I have not been able to confirm or refute.

Figure 2. A photo from a correspondent of a probable Morrill. The clock bears many of the hallmarks of Morrill's work, so it's an attribution. Unfortunately, the clock's provenance is a total mystery.

The Henniker clock's time train is closely patterned after a flatbed clock illustrated by Lepaute in his 1767 Traité d'Horlogerie. The French flatbed design was first used in this country in 1799 by Abel Stowell, Sr. in Worcester, Massachusetts. Morrill used the wood-frame table pioneered by Stowell, but did not copy Stowell's platform base for the frame. The Henniker clock frame is 31 1/2 inches high, 26 1/4 inches deep, and 52 1/8 inches wide, made of 3 x 3 1/4 inch square beams of rock maple, with all joints mortised, tenoned, and fastened with wood pins. There is no decorative beading on the beams. The top beam ends are neatly rounded off in a form Frederick Shelley has christened the 'New Hampshire bumper'. All four legs are fitted with wood braces. Morrill used a mid-beam to support the shorter, stronger arbors for both trains, and, in this clock, placed the winding drums on top of the table. The time train is extremely simple, consisting of a barrel wheel with winding drum, a second wheel, a pinwheel, the escapement pallets, and the transmission drive system.

Figure 3. The Henniker clock now in the American Clock and Watch Museum in Bristol, Connecticut. The inverted 'L' above the clock carried the transmission capable of driving four dials.

Morrill's contemporaries almost invariably used an intermediate (or third) wheel in the time train, allowing lower tooth counts on each of the wheels. The tooth counts on the wheels and pinions of the Henniker clock are unusually high, particularly on the escape pinwheel---it has 46 pins around its rim, which impulsed a 1.9 second pendulum. Regulation of the pendulum was accomplished via the (un)usual rating nut under the 9 inch diameter, lenticular pendulum bob.

Figure 4. The fancy rating nut found on the Cooke, Henniker, Orford, and Sugar Hill clocks.

The crutch is a rather long and slender steel rod engaging an unlined slot in the hardwood pendulum rod. There is no provision for maintaining power. The 30 (not the 29 Parsons specifies) strike lifting pins are planted on the inner face of the strike main wheel, the second strike wheel arbor is fitted with a three tooth gathering pallet, and the

3 Parsons very kindly provided the tooth count for this clock: "Great wheel, 120, driving a pinion of 10; the second wheel of 120 driving a pinion of 12; the pinwheel has 46 pins. An 18-tooth bevel (sic) gear on the first wheel arbor drives a 36-tooth wheel, whose 6-tooth pinion drives the 72-tooth hour wheel. Solving for vibrations per minute yields a pendulum length of nearly 14 feet---approximately two seconds (actually 1.956 seconds). Why Morrill used 46 pins in the pinwheel, I have no idea. A 45 pin wheel would have been easier to lay out, and would have driven a 2 second pendulum.6

ratchet drive for the strike train fan is fitted on the collet of the third wheel, instead of on the fan itself. The compact, yet rather wide and heavy fan may have been used as a combination air resistance and weight resistance governor. The horizontal strike rack has not been noted on any other contemporaneous clocks. The French, for some reason, clung to the count wheel system for many years; the English used both the count wheel and the rack and snail, and most early American tower clock makers used a rack and snail system which appears to merely be an enlargement of the familiar tall-case rack and snail. Morrill placed an 18 tooth gear on the non-working end of the second wheel arbor to drive a 36 tooth minute wheel which carries the trip lever for the hourly strike. The minute wheel and its six leaf pinion drive the strike snail and the motion work for the (unsigned) setting dial hands. A bevel gear on the second wheel arbor drives the vertical shaft to the transmission; the transmission bevel gear carrier is all that remains of the transmission. The transmission support post, shaped like an inverted 'L', is still attached to the frame. Parsons noted that the motion work hour wheel had 72 teeth, driven by a 6 tooth pinion and two wheels of 36 teeth, but mentions nothing about the spoking of the wheels. The bearing blocks are very nicely executed, rather than being merely utilitarian. The weights no longer exist, nor are any of the motion works, dials or hands available for examination. The hands, according to Parsons, were 291/2 and 385/8 inches long with an internal counterpoise on the leading-off rod. The time side winding jack and the setting dial hand, shown in Parsons' photographs, were unaccountably missing when the latest photographs were taken in the American Clock and Watch Museum at Bristol.

The DOVER Clock

First sight of the First Parish Church in Dover wasn't very encouraging---the hands on the south dial facing the parking lot were Howards. The church secretary handed me the key to the clock room and pointed out the door to the stairs. On reaching the attic floor below the clock the first evidence that it really wasn't a case of mistaken identity was the typical Howard pendulum box, and the all-pervading killer-bee-hum of one of those horrid little Bodine motors---with bad bearings. It was one of Howard's æsthetic failures, a round-top with all the electrical bells and whistles foisted on tower clocks by those who would have us believe that in "Electrification is Preservation". A thorough

7

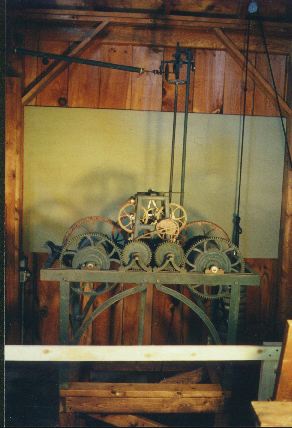

search of the clock room and the floor around it revealed nothing of the original Morrill clock, just a pile of parts removed from the Howard for its electrification4. On my way back down the ladder, a disheartened glance off into the shadows of the attic floor below landed on an old hand---then two hands---and another jumble of clock parts.

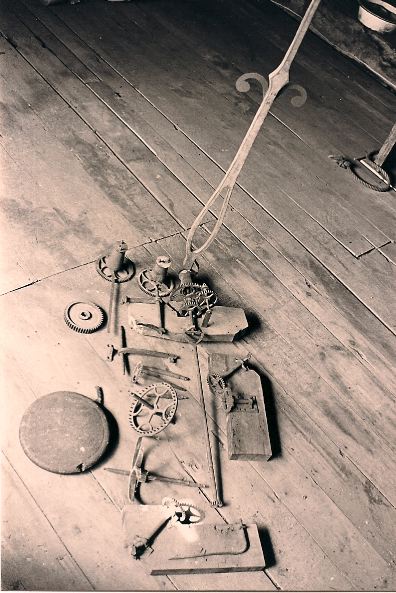

Figure 5. All that remains of the Dover clock. Note that the hour hand carrier at

the upper left has an internal counterpoise---very unusual on any tower clock.

In this pile were the remains of three very old, and very unusual, motion works; the time train second wheel arbor with its 10 leaf pinion and a broken spoke or two with a mere fragment of the rim, the pinwheel, the pallet arm and arbor, the strike lock lever, one forged leading-off rod, several motion work arbors with half of the fork universals still attached, the pendulum bob, two nuts---one in brass, one in steel---and one brass bearing block. Off in a far corner, behind a pile of wooden pedal (lowest register) pipes from the organ, were the two winding drums and great wheels. Benjamin Morrill's first tower clock was a jumble of junked parts.

Figure 6. The'working' end of one of the winding barrels, illustrating

the decorated cast-iron endcap Morrill used on his early clocks.

The notes cited above in the Dover Town Records: "winding and caring for old clock", and " winding and repairing old Town Clock, '68 and '69", suggest either extensive repairs to the Morrill or that a new clock had been installed at that time. A pamphlet titled Rambles about the Dover Area, 1623 - 1973, claims that the Morrill clock functioned well "for about 25 years and then began to give trouble and then stopped for good", but 1868 is too early for a round-top Howard, a model which appeared a few years later. The earliest New Hampshire record of a round-top installation I can find is 1871. Even though the 1868 through 1871 Dover records for clock care suggest that the clock might have been replaced at that time, a study of photographs of the church and known dates of its external alterations suggest that the Howard was installed sometime between 1870 and 1880. The motion works for this Howard are the early ones, with large spoked wheels.

Figure 7. A side view of the same winding barrel, showing the recess for the knot in the

weight line, the cast-iron main wheel and ratchet, the click, and the decorated click spring.

4 For the watch and clock collectors who read this: An electrified tower clock is usually driven backwards from the 'scape wheel arbor to the minute arbor. Since wheel trains are designed to minimize engaging friction between wheel and pinion, reversing the drive direction changes disengaging friction to engaging friction. Just try to imagine how long your favorite grande complication would last with this sort of treatment. There are conflicting theories on whether any damage is done to the clockworks, but at its best, which also seems to be its worst, electrification is often little more than a death sentence. The end result is that the clock is usually maintained (read oiled) but once a year. If electrical power is lost and then restored, the hands are usually merely reset. I have seen electrified clocks with six-inch extrusions of dirt and dried oil at each pivot. Older Bodine motors also have a bad habit of starting up backwards when power is restored, which jams the strike trip lever...Why not just put in a Simplex with electronic chimes?---or restore the clock to weight drive with electric re-wind?8

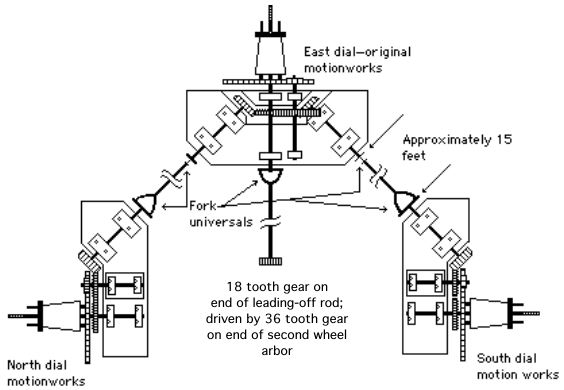

The parts in that pile were from the original 1835 clock. The circular spoking of the barrel wheels and of the remnant of the second wheel, the spoking on the pinwheel, and the construction of the pallet arm are diagnostic. That the clock originally had but one dial is confirmed by the single very short leading-off rod, and a nicely finished bricked-in oval opening to the back of the dial in the east wall. Evidence that the other two dials were installed later can be seen in the openings in the wooden walls behind the north and south dials; these openings are rather crudely cut, and in the remains of the original motion works installation. A measurement from the back of the east (front) dial to marks on the dropped floor of the (original) clock room indicated that the clock was installed very close to the front of the church, with the top of the frame at the level of the center of the east dial. Any further speculation about two later dials was put to rest by the oddly built north and south dial motion works.

Figure 8. The top motion works drove the original east dial, the other two drove the north and south dials.

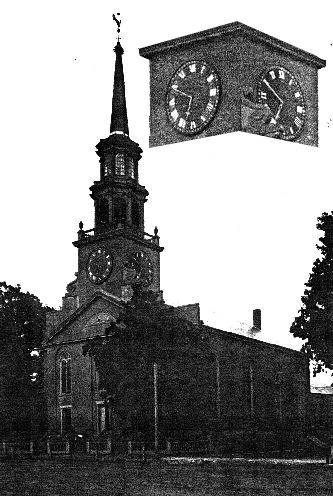

These motion works with bevelled input drive gears were designed to compensate for the clock's installation in very close proximity (within 3 feet) to the front wall. A rough approximation of probable clock and actual dial positions yielded a length of nearly 15 feet for the north and south leading-off rods, and the 45° angles lined up nicely. That the front dial bore the IV form and the side dial(s)---in a photograph from the 1860's---bore the IIII form for 4, (implying different installation times for the side dial[s]) is confirmation that originally there was but the one dial, and that the maker of the later dials wasn't paying attention. The dials have since been renumbered; all three now bear the IIII form for 4.

Figure 9. A photograph of the Dover church from the 1860's. In the inset, the front dial can be seen to have the IV form for 4, while the north dial uses the IIII form.

9

an internal or external counterpoise for the minute hand, but the hour hand has an internal hour wheel counterpoise mentioned above. The method used for setting the outside dials will very likely never be known, because the clock frame and the escapement supports have disappeared. There was neither a winding handle nor a winding gear to be found to fit the tapered winding squares on the drums. The winding squares are an inch square at the drum end, and taper down to 5/8 inch at the outer end of the 5-inch long square. A small cast iron wheel with 48 teeth may have been a part of a winding jack.

5 Tooth counts: minute wheel of 36, pinion of 18 on the end of the leading-off rod; second wheel of 120; pinion of 12; pinwheel of 40; 2 pallets. This is:

36 x 120 x 40 x 2 = 345 600 = 26.667 vibrations per minute.

18 x 12 x 60 12 960

60 = 2.25 seconds.

26.667

If the second wheel had fewer than 120 teeth, the pendulum length would increase. For instance; if the second wheel had only 96 teeth, the pendulum period would increase to 2.8125 seconds---25.8 feet!10

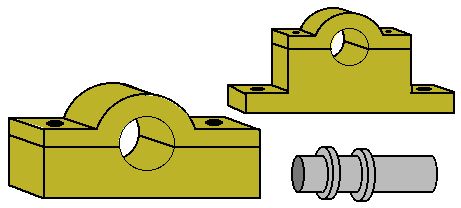

Figure 10. Split bearing blocks found on Morrill clocks, and a section of motion work arbor with turned locating rings.

Sic transit gloria Morrilliana.

11

A MOTIONWORK SEAT-BOARD-BASED TRANSMISSION;

a novel solution to drive the two new dials

6 Footnote 5 discussed the tooth counts of the time train to establish the pendulum length. In that the 36 tooth minute wheel is driven by an 18 tooth gear, the second arbor must have had a 36 tooth gear driving that gear, so the second arbor made two turns per hour. A 2.25 second pendulum falls within reasonable parameters for the clock. If the second wheel drove the motion works on a 1:1 ratio, the pendulum length would be unreasonable.

7 The very late (1850) Holbrook in East Medway, MA., (now Millis, MA) is an exception in that it has a secondary transmission to drive two dials well above the level on which the clock is installed, but still has only three dials. (Frederick Shelley, unpublished MS.)

12

Figure 11. The top motion works drove the original east dial, the other two drove the north and south dials.The addition of the half-bevel gears, the two leading-off rods. and two new motion works solved all the problems of driving the two new dials. All in all, it's a clever solution to a sticky problem, and could have been adapted to drive a fourth dial from either of the 'new' motion works merely by installing the appropriate angled drives to the fourth dial. If Morrill had used his vertical drive to a transmission for ths clock, he would have had to build and install the transmission; the floor of the clock room would have had to be dropped considerably, the clock would have had to have been moved back to the center of the clock room, (even a conventional universal joint will jam at extreme angles, much less the fork universal) and three complete new leading off rods would have been required.

The ORFORD MORRILL

13

Figure 12. The West (or Orford Street) Church that carries the clock in its steeple. It is the only wooden Gothic church in New Hampshire.

Figure 13. The clock in the West Church, attributed to Benjamin Morrill, after its restoration.An exhaustive search for documentation of the date of installation and corroboration of the name of the maker has drawn almost a total blank. Unfortunately, both the town and the church historians carefully detail the church's history until the 1801-1833 ministry of the Rev. Mr. Sylvester Dana8, and only resume the church history some years after the Rev. Mr. Dana's dismission due to old age, during the tenure of his successor. Town Records have also yielded (to date) only three cryptic entries: 1851---A. Phelps, cleaning the clock, 50¢; 1854---Adolphus Phelps, cleaning the clock, 50¢; March 21, 1881, A. Phelps---cleaning the clock, 50¢. The church building is the fifth used by the congregation, the fourth on the same site, and was built between 1850 and 1854. The first town meeting house and church in Orford was a remodelled storage shed. The second meeting house was built on the current site as a church, which, interestingly enough, when it was deemed no longer serviceable in 1820, was moved off to one side, where it sat for several years. It was later taken apart and floated down the Connecticut River to the town of Norwich, where it was repaired, rebuilt, and served as the Episcopal church until it was destroyed by fire in 1917. The dates and the fate of the third church building are not known, but it could have been the first to house the clock in its steeple. The history of this church building coincides with the tenures (and the missing church

8 Penrose Hoopes places the Bristol, Connecticut, clockmaker, Gideon Roberts, in Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley, site of the Wyoming Massacre, contemporaneously with the young Dana. Small world...

9 The History of Orford states that the church was begun in 1851 and finished in 1854. The History of the Orford Church claims the church was completed on December 31, 1850, and dedicated the following month. Research continues...but the question arises as to whether the clock had been installed in this church's predecessor. If not, then why was the clock cleaned in 1851? The West Church records for the years 1833 - 1842 somehow disappeared at some time in the 1880's.

10 The reuse of the building fits in rather well with the New Englander's maxim; "Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without." Mrs. Hodgson, in her Orford, New Hampshire, A Most Beautiful Village, avers that this building was used as the Episcopal Church in Norwich, Vermont. The Rev. E. D. Harvey in his History of the Orford Church, in turn, avers that this building was used in the construction of the Norwich Congregational Church, which would not be possible. The Norwich Congregational Church had its tower clock installed and running in 1816.

14

The ORFORD Clock

15

11 The tooth counts on the motion work wheels are a departure from his other clocks: a 30 tooth pinion drives a 60 tooth intermediate wheel, whose 12 tooth pinion drives a 72 tooth hour wheel.

16

The SUGAR HILL MORRILL

Figure 14. The Sugar Hill clock. It was missing the vertical drive rod and the transmission carrier still had not been located.

Figure 15. The clock after the transmission carrier and the drive rod had been found and mounted. Two partial and one complete motion works were later located in Littleton, New Hampshire, and re-united with the clock.

17

18

Figure 16. The 1839 Advent Church that originally housed this clock. The church has since been deconsecrated, and now serves as the Town House.

19

The SUGAR HILL Clock

The clock is small in comparison with its fellows, and the frame is entirely of metal. The top of the frame stands but slightly over 2 feet---251/4 inches, is a mere 201/2 inches wide and 443/8 inches long. The paint is a faded light blue, a departure from the dark green used on the Henniker and Orford clocks. Two winding jacks are permanently installed, driving wood drums with the characteristic circular spoking seen on all Morrill's clocks. The trains are carried in a central frame rising from the flatbed, time on the right and strike on the left. Morrill's inverted 'L' transmission carrier rises above the clock, bolted to the frame, and braced on the central frame. The carrier, with a vertical drive rod, is configured for three dials, but has provision to drive a fourth. The escapement is a pinwheel, with 18 steel pins, and the pallets are a steel arc swinging inside the pins.

Figure 17. The clock installed and running, time only, at the Sugar Hill Museum, Sugar Hill, New Hampshire, with the original dial and copies of the hands.

Figure 18. A side view of the clock after its installation. The time train is on the right, strike on the left.The strike train is a dead copy of the strike train of the Orford clock, with a few improvements. The cast-iron wheel teeth all look alike---they are cleanly cut---and almost look as though they were hobbed, rather than hand-filed, which was the then-accepted method of cutting teeth. Tooth counts are identical to those of the Orford clock. Review the "Similarities" above---they are telling. The glaring exception is the use of a conventional rack in the place of Morrill's signature horizontal rack, but there just isn't room for the horizontal rack.

A Summation---and a possible early MORRILL clock.

20

MORRILL, The Practical Æsthete

Figure 19. A view of a Holbrook I restored in Chelsea, Vermont.

Its overall appearance is more blacksmith than clockmaker.

12 I am not picking on Holbrook. He was merely a contemporary maker of somewhat similar clocks.21

BIBLIOGRAPHY

22

Return to Page Three of the late Donn Haven Lathrop's three main pages.

Donn's original version of this page was inaccessible because of a mis-named directory.

To comment on this page, please