3 His grandson wrote in 1876 that the

apprenticeship years were spent in Salem, MA, (which seems to be highly

unlikely) while Dr. Currier avers the apprenticeship was in Haverhill,

MA. I suspect that his grandson is incorrect---both Michael and Dudley

Carleton worked in Haverhill and its suburb, Bradford, MA.

4 All accounts written to date put Osgood in

Haverhill as late as 1795, or "prior to 1795." However, that date is

merely the year he was elected as Sealer of Weights and Measures. The

discovery of this advertisement corrects a long-standing error.

2

A bit of geography; Coos (pronounced k´· oös) originally Cohos or

Cohoes, and sometimes Coös---even Cowass---is now the name of the

northernmost county in New Hampshire. Haverhill, incorporated in 1763,

was the original county seat. Before the final county boundaries were

drawn in 1803, the entire area along the Connecticut River, from

Charlestown, or Fort #4---the first settlement in New Hampshire---in the

south to an undefined area in the north was known as Coos. Osgood's

move to Haverhill may well have been influenced by his other "uncle",

Dudley Carleton, already established as a cabinet-maker across the

Connecticut River in Bradford, Vermont, who later made many of the cases

for Osgood's tall-case clocks.

Two years later Osgood was elected Haverhill's Sealer of Weights and

Measures, therefore he must have very quickly established himself as a

reputable businessman in the community. Business must have been rather

good, as attested to by the following advertisement that appeared in the

[Concord, NH] Mirrour for 27 February, 1795:

Wanted, For three, six or twelve months, A Journeyman Clock

Maker, Who is a good workman---to whom generous wages will be given by

the subscriber. John Osgood.

Haverhill, Coos, Feb 16, 1795.

On 4 March, 1797, John Osgood married Sarah Porter, whose parents,

William and Mary Porter, had moved to North Haverhill from Boxford,

Massachusetts, in 1790. The couple had seven children, all born in

Haverhill, where Osgood also served as town clerk and town treasurer for

several successive terms. He also did well in accumulating property;

not only did he own the house and shop in town, but a farm located on

the eastern edge of town. This farm, with William Porter, brother to

Mrs. Osgood, installed as caretaker, was close to Tarleton Pond (now

Lake Tarleton), where Osgood could indulge in his passion for fishing.

His youngest daughter, Charlotte, married Daniel Blaisdell, a lawyer and

politician of Hanover, New Hampshire, who also served as the Treasurer

of Dartmouth College for forty years. John Osgood, Jr. became a clock-

and watchmaker--predominantly the latter--a trade he pursued in

Boston until his death in 1860. Only one clock by the younger Osgood is

known.

3

Figure 5. Two toys, cut from a sheet

of tin, that Osgood made for his grandson. The toys were attached to

the stovepipe with a bent wire, and would spin in the rising hot air.

Sketch from the Blaisdell Manuscript, courtesy Mr. Howard Evans.

Rev. William F. Whitcher, the Haverhill Town Historian,

quoted Osgood's grandson, Alfred Blaisdell;

"He [John Osgood] was rather below the medium height, very

quiet and unobtrusive, but genial and sociable...he was offered the

position of Deacon in the Congregational Church, a position he declined

because of a slight lameness which he deemed unfitted him for the duties

of the position. He was a devoted disciple of Isaac Walton, and

Tarleton Pond, as it was then called, had great attractions for him. He

lived for a time in the Nathaniel Bailey house, where he carried on his

work until the demands of his business led him to build a shop across

the way, almost directly west of the Bailey house. This was a square,

one story building with two windows in front between which was a 'Dutch'

door. On the lower half he liked to lean to chat with those passing

by. There were two rooms; in front, a salesroom, and in back, his

workroom where there was a forge for melting the brass for the clocks

and the old Spanish dollars for the spoons, buckles, etc. In his later

years, Osgood built a house which stood north of the Exchange Hotel, on

Main Street. All this, some years back, was burned in a fire which

consumed the hotel and other buildings."5

from a hand-written and hand-illustrated manuscript

by Mr. Blaisdell of his reminiscences concerning John Osgood, his

grandfather, set down 36 years after his grandfather's death6.

The manuscript makes for some rather fascinating reading, but

unfortunately says very little of Osgood's clockmaking activities. The

slight lameness mentioned above was the result of a "white swelling",

also known as tuberculous arthritis7, that eventually

resulted in a near-total loss of joint mobility. Mr. Blaisdell

expresses regret that after his grandfather's death many of the lead

patterns for knee and shoe buckles were melted down to make small

hatchets for his amusement, and that,

5 Rev. W. F. Whitcher:

The History of Haverhill, New-Hampshire., Ppg. 609-610.

6 From Mr. Blaisdell's original handwritten

manuscript. Unfortunately, the reminiscences commence when the author,

the son of Osgood's youngest daughter, was only seven years old.

Even though they are not of a technical nature, they do provide a good

glimpse of Osgood in his later years.

7 From Merck: "Tuberculosis of Bones and Joints:

When primary TB occurs during childhood while the epiphyses are open and the

blood supply is rich, bacilli often disseminate to the vertebrae and the

ends of the long bones, where disease may develop either then or months,

years, or decades later...the joints most commonly involved are those that

bear weight, but bones of the wrist, hand, and elbow also may be involved,

especially if they have been traumatized."

4

probably because his heirs were not at all mechanically minded, "...all

tools and personal property were sold at auction and disappeared

forever.", regardless that many years later his grandson spent a good

deal of time searching for them.

|

Evidently some of these guns were

sold by Blaisdell's uncle Alfred in St. Louis, Missouri. This uncle,

John Osgood's second son, had moved to St. Louis, Missouri, many years

earlier to engage in the hardware business, and was killed in 1852 on

the Mississippi River when the boiler of the steamboat on which he was

travelling exploded.

Osgood was quite a prolific maker, according to his numbering

system---the highest number found to date is #313. We can safely assume

that Osgood was at work for some 49 years, from 1791 to 1840. If he

indeed did make 313 clocks, that would average out to just over six

clocks a year---well within the realm of possibility---on which more

later. He numbered his clocks on the back plate of the clock movement,

a practice followed by his apprentice9, Phinehas Bailey.

All of these clock movements, whether timepieces, or time and strike, are

tall-cased. The sole known exception is the gallery clock he made in

1838, very likely his last clock, as he was then 68 years old. His only

known apprentice was Phinehas Bailey, whose Memoirs prompted this

research on him, and as a consequence, on the lives and relationships of

the other clockmakers discussed

8 This may be the shop of Osgood's other "uncle",

Michael Carleton, but no corroborative data has been found.

9 The Bailey clock illustrated in the article

on Bailey (BULLETIN #315, Pg. 461) is numbered 28. The Blaisdell

manuscript relates that there were several apprentices and journeymen

working for Osgood, but none of these names have been recorded.

5

in this series of papers. His son, John Jr., may also have been his

apprentice. Mr. Blaisdell recalls that his grandmother mentioned the

names of several apprentices or journeymen, but he does not remember any

of their names.

It is known that Bailey joined three other apprentices10

at the time of his apprenticeship with Osgood.

In 1797, Osgood further advertised:

A Journeyman Clock Maker, who is a good workman, may find

good encouragement to work by the month or movement, at his shop in

Haverhill, Coos.

A boy, 14 or 15 years old, is also wanted, as an Apprentice to the above

mentioned business, and may have good encouragement by applying to me.

John Osgood.

Courier of New Hampshire, March 21, 1797.

Osgood was not only a clockmaker, and a gold- and silversmith, but a

valued member of the town. He not only served as the Sealer of Weights

and Measures, but was also at one time or another the Town Clerk, the

Town Treasurer---all of these were elective posts---and for many years

was a member of the Board of Trustees of the Haverhill Academy. John

Osgood, clockmaker, silversmith, goldsmith, and town officer, died at

the age of 70 in his home on 29 July, 1840, of consumption. It is

likely that Osgood contracted tuberculosis early in life and as Footnote

7 indicates, it may be decades before the disease fully manifests

itself.

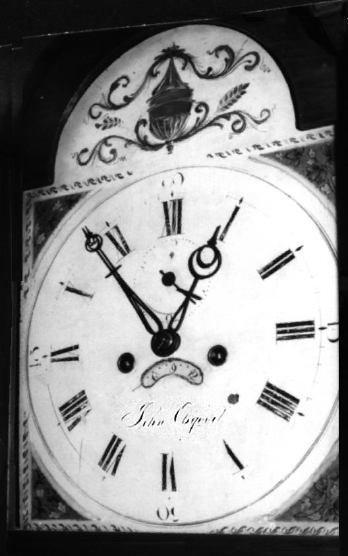

Figure 7.

The floor plan of Osgood's house.

The small bedroom just off the kitchen is likely where he died.

Sketch from the Blaisdell Manuscript, courtesy Mr. Howard Evans.

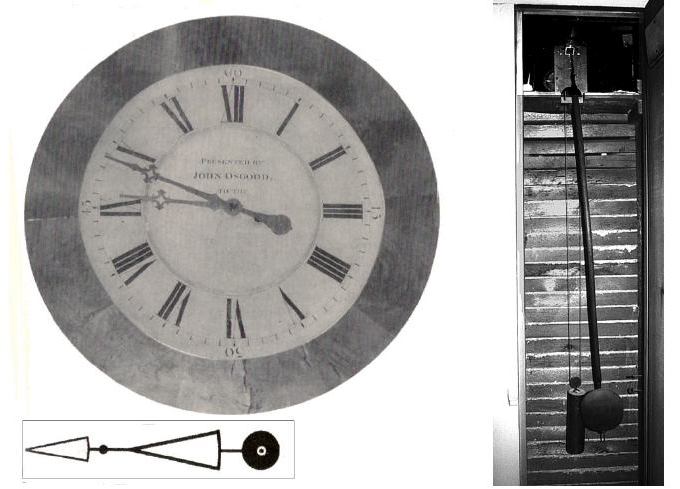

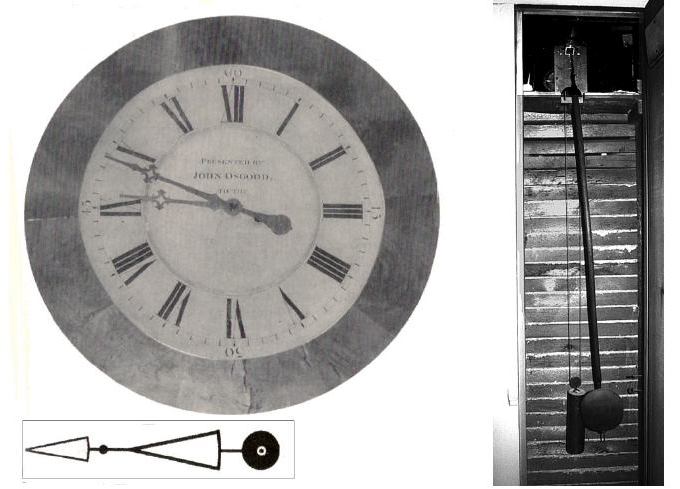

The gallery clock fell into disrepair over the

years, and by 1950 had been still for some time. A photograph in the

cited article in ANTIQUES Journal shows it missing the minute

hand---whatever other faults it may have developed are unknown. It was

finally "repaired" in the early 1960's---with an added electrical drive

to replace its original weight drive---but the hands are replacements.

The movement has since been restored to its original condition---the

electrification has been removed---and the clock is still keeping time,

these 170 years later.

10 Bailey is the only named apprentice.

Bailey's eldest daughter, in her undated manuscript; A Father's Legacy, writes:

"He found in Mr. Osgood's shop three other apprentices who were to be

his most intimate associates for some time to come." Who these

apprentices were can only be the subject of speculation.

5

Figure 8. The

gallery clock, signed John Osgood, given to the then "First

Congregational Church & and Society." The original hand form is

inset at lower left. On the right is the back of the clock, showing the

movement, the weight and the pendulum.

Photographs courtesy of Mr. Carlton Elsner.

It may seem odd to the reader that Osgood is

credited with the prodigious output of some 313 clocks, if his numbering

system is to be believed. A quick examination of the particulars of

his life and locale may somewhat alleviate the disbelief.

Osgood began his clock-making in 1791 in Andover and Haverhill,

Massachusetts. At least two clocks from Andover are known.

Unfortunately, the Haverhill, Massachusetts, and the Haverhill, New

Hampshire, clocks cannot be distinguished, other than perhaps through a

detailed examination of various early and late movements, and a

cataloging of the changes in construction as his style matured.

The population of Haverhill, New Hampshire, was about 550 in 1795,

rising to 875 in 1800, and 2,183 in 1830. Just across the Connecticut

River lay the Vermont towns of Bradford and Newbury, and just to the

north was the town of Woodsville. In that the majority of the

population were fairly recent immigrants and likely hadn't brought a

clock with them on their travels, Osgood may have had a captive buying

audience. His working life was about 47 years, if we accept that the

gallery clock dated 1838 was indeed his last, and 313 clocks spread over

those 47 years works out to just over 6 clocks per year.

Phillip Zea11

notes that Jedidiah Baldwin sold six tall-case clocks in 1795, just a

few miles south in Hanover, New Hampshire, although he was not able to

maintain that output level even with a population level nearly thrice

that of Haverhill. In the 18 years from 1793 to 1811, Baldwin made a

known 55 clocks, just over 3 per year, but his sales may have been

curtailed somewhat by the more or less transient nature of the

population surrounding Dartmouth College. The thought occurred that

Osgood was able to make a profit by charging less for each clock, and

making up the difference in quantity, but an original (date unknown)

bill of sale for an Osgood clock records a charge of $30 for the

movement, and $35 for the case, while Baldwin was known to charge $33

for the movement and $20 for the case. Dr. Currier wrote that he knew

of 27

11 To Making one of Saturn's Moons:

Jedidiah Baldwin and the Urbanization of the Upper Connecticut River Valley,

1793-1811. Pg. 27.

6

Osgood clocks in 1960, and that Osgood had been commissioned to make

five clocks at one time for the Stevens family of Haverhill.

Unfortunately, all of Osgood's records disappeared after his death.

Osgood appears to have been a thoroughly conventional maker. He made

timepieces, conventional time/strike clocks, and clocks with moon phase

dials, but evidently was not a maker with an horological curiosity that

led him into experimentation and the construction of unusual clocks.

Dr. Currier notes that the gallery clock made in 1838 has a movement

nearly identical to the earliest known clock made nearly 50 years

earlier. Of the 27 (about 9% of the total) clocks Dr. Currier examined,

2 (7%) were timepieces, 4 (15%) were moon phase, and the other 21 (78%)

were conventional time/strike. The Osgood clock illustrated in

Parsons' New Hampshire Clocks and Clockmakers (Figs. 191-196) has

a thoroughly conventional movement that accomplishes the intended task

of telling time and striking the hours without any embellishments

whatever.

Perhaps we can conclude that Osgood's success with his clocks reflects

his long stay in the same town, his acceptance as a reliable and worthy

businessman and Town official, and the New Englander's philosophy of

simplicity and usefulness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my particular appreciation to Mr. Howard Evans

for his kind permission to use the illustrations from the Blaisdell

manuscript, and to Mr. Carlton Elsner, who took the trouble to search

through his files for the photographs of the Osgood gallery clock, and

of his Osgood tall clock.

Just a foot note to Carlton's life: He was the sole (and volunteeer)

caretaker of the 1844 Stephen Hasham tower clock in the Congregational

Church, making the trip to the clock room weekly for 25 years, and

funded many of the clock repairs out of his own pocket. That was how I

met him---the clock needed repairs---as did some of his own clocks, and

formed a friendship that I treasure. Carlton died at the age of 87 this

past summer. He will be missed.

Bibliography:

BITTINGER, John Quincy, History of Haverhill, N.H.,:

Haverhill, N.H. [Cohos Steam Press] 1888.

BLAISDELL, Alfred Osgood, Handwritten manuscript: His recollections of his

grandfather, John Osgood, of Haverhill, New Hampshire.

Brooklyn, New York, 1876. Courtesy Mr. Howard Evans,

who also permitted the use of the illustrations.

CURRIER, Dr. Charles A., John Osgood, Clockmaker of the Merrimack and Connecticut River

Valleys (as told to Brooks Palmer).

The Antiques Journal, Babka Publishing Company, Dubuque, Iowa.

January, 1960.

FILLION, Robert G., Haverhill Corner, (N.H.) National Historic District:

Privately printed by Robert Fillion, Woodsville, N.H. 1991.

HARRIS, J. Carter, The Clock and Watch Maker's American Advertiser (1707-1800).

Unpublished manuscript held at the NAWCC Library. 1984.

MEMOIRS of Rev. Phinehas Bailey, written by himself.

Incomplete 55 page typescript transcribed 1902 by Louisa M. Bailey (Mrs. Joel F.) Whitney.

Courtesy the Vermont Historical Society.

MEMOIRS of Rev. Phinehas Bailey, written by himself. These five pages were evidently

edited out of the Vermont Historical Society typescript (perhaps in an effort to

remove the family's domestic difficulties from the public eye) and are found in this

manuscript (transcriptionist unknown) held in the collections of the Bennington Museum.

Courtesy the Bennington Museum.

PARSONS, Charles S., New Hampshire Clocks and Clockmakers.

Adams-Brown Co., Exeter, New Hampshire. 1976.

WALBRIDGE, John Hill, compiler, The Town of Haverhill:

A History of Haverhill and Wells River to 1897.

Privately printed by Robert Fillion, Woodsville, N.H. 1991.

WHITCHER, Rev. William Frederick, History of the Town of Haverhill, New-Hampshire.

Rumford Press, Concord, New Hampshire. 1919.

WHITNEY, Louisa M. (Bailey), A Father's Legacy, an undated, unpublished typescript

(transcriptionist unknown) manuscript.

An uncritical and highly edited biographical treatment of Phinehas Bailey.

Courtesy of the Vermont Historical Society.

ZEA, Phillip, To Making One of Saturn's Moons: Jedidiah Baldwin and the Urbanization

of the Upper Connecticut River Valley, 1793-1811.

Unpublished manuscript held in the Special Collections,

Baker Library, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire. 1979.

Return to Page Three of the late Donn Haven Lathrop's three main pages.

Compare Donn's

original version of this page

if it still exists.

To comment on this page, please

|